There’s a bit of pirate in everyone – a love of the water, a sense of adventure, and a wink of defiance about following rules. Maybe that’s why we’re drawn to stories about the swashbucklers who roamed the seas.

Movies and folklore tend to focus on pirates of the Caribbean, so most people don’t realize that the Chesapeake Bay hosted its share of scallywags and wenches. But why would they choose the waters of Maryland and Virginia when the Atlantic and Caribbean were teaming with treasure-laden ships and ports to plunder?

Several factors made the region a hot-spot for pirates. After months of raiding and pillaging, battle-weary buccaneers ran out of supplies and their ships took a beating. The Bay’s isolated necks and coves provided ideal sanctuaries to make repairs and restock stashes of food, water, and other necessities.

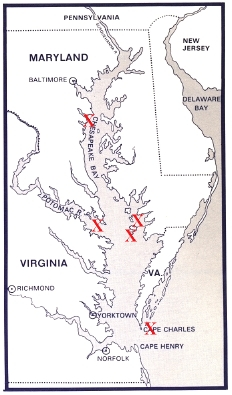

Red “Xs” on the map show pirate bases on the Bay. — Maryland with Pride Web Site

Plus, pirates also didn’t meet much resistance when they cruised into the Bay. In the early 1600s, England and Spain were jockeying for control of the New World, but were often occupied with their own troubles in Europe and didn’t commit ample resources to protect their fledgling colonies. Settlers half-heartedly built forts but were more concerned about surviving famine, disease, and Indian raids.

As the Maryland and Virginia colonies flourished, ships passing through the Bay to and from Europe became filled with treasures that made pirates rub their eyepatches in glee. Capturing a merchant ship that carried a cargo of tobacco, food, wine, linens, or gold was cause for wild, and often drunken, celebration.

Like a school of piranhas devouring a carcass, pirate crews would strip their prey of sails, rigging, and tackle. Sometimes they’d set a crippled vessel ablaze, just to watch it burn. Passengers were forced to join pirate crews or tortured to cough up secrets about royal war-ships in the area.

If scallywags overtook a ship that was newer or faster than their own, they’d add it to their fleet. This was a huge source of frustration for the Governors of the Colonies, who would convince the king to send battleships to defend their subjects, only to be outgunned and overpowered by invading sea dogs.

We’re Not Gonna Take It

Some colonists liked to trade with pirates, exchanging fresh water and provisions for more exotic stolen items such as spices, clothing, or rum. Other colonists became fed up with marauding scoundrels and took matters into their own hands. Take the case of the dreaded Monsieur Peuman, a French privateer infamous for pillaging farms and towns along the Rappahannock River near Port Royal, VA, in the mid-1600s.

At wit’s end with Peuman’s looting, villagers formed a search party to capture the pirate. When Peuman entered the river with thieving on his mind, the townsfolk chased his ship upstream. He veered into a creek to evade them but got stuck in shallow water. The angry mod jumped on board, slew the Frenchman, and named the creek “Peumansend” to mark the place of his demise and send a warning to other scalawags.

Three Pirates’ Prize is a Blessing in Disguise

By the late 1600s, it was time to crack down on piracy. England’s King James unleashed a brigade of royal navy ships to clear out the scoundrels who terrorized the Chesapeake, Caribbean, and Atlantic. In 1684, the King issued a pardon for pirates who turned themselves in to authorities and rejected the pirate way of life.

The previous year, a trio of seasoned privateers named Davis, Wafer, and Hinson had joined Captain John Cook in Accomac, VA, to sail the South Seas. “They had attacked and taken towns and ships, crossed the steamy jungles of the Isthmus of Panama on foot, were befriended by savage jungles natives, and wrought unending chaos on the Spanish colonists of Tierre Firme,” says Donald Shomette, in Pirates of the Chesapeake. They cruised around the globe, amassing a considerable pirate’s bounty along the way.

Captain Cook passed away during the voyage, but the three buccaneers eventually returned to the Chesapeake Bay, hoping to settle down and retire as wealthy men. Near the mouth of the James River, they were apprehended by Captain Rowe of the Dumbarton and tossed in the Jamestown jail. The deal arranged for their freedom required them to hand over their stolen loot, which Virginia authorities used to establish the College of William and Mary.

Chesapeake Rogues of the Sea Came in All Shapes and Sizes

The Golden Age of Pirates reached a peak from 1690 to 1730. Despite popular perception, “Life aboard a sailing ship was anything but comfortable. Seamen lived in cramped and filthy quarters. Rats gnawed through anything, including a ship’s hull. Food spoiled or became infested, and fresh water turned foul,” says Cindy Vallar, in Pirates and Privateers, The History of Maritime Piracy.

Life expectancy for a Chesapeake privateer was short. Fierce storms sunk scores of ships, and diseases such as scurvy, dysentery, and smallpox ran rampant among the crew. But the opportunity to make a mint in pirate booty and live a life of adventure proved irresistible for many fortune-hunters on the Bay.

Blackbeard (aka Edward Teach)

One of the most formidable pirates was Blackbeard (aka Edward Teach). According to legend, he captured 40 ships in his day, and his physical appearance sent fear running down his enemies’ spines. Blackbeard towered at 6’5”, with a jet-black beard that grew down his chest and was braided with brightly colored ribbons. He placed slow-burning wicks in his hair and lit them to create a smoky, demonic look in battle. A bandolier crossing his chest with six pistols was the finishing touch to his horrifying attire. He drank rum spiced with gunpowder.

The Eastern Shore was Blackbeard’s favorite haunt for mending damaged ships, and he delighted in plundering local plantations en route back to the Atlantic. He roamed as far north as Pennsylvania, but loved to dodge British ships by hiding in Pagan Creek off the James River or in the remote corners of Lynnhaven Bay.

Blackbeard’s pillaging days came to a screeching halt in 1719, when Lt. Robert Maynard fatally shot him in a bloody fight off North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Maynard severed Blackbeard’s head and mounted it on his ship’s bow.

For years, the skull hung from a pole where the Hampton and James Rivers meet to warn other pirates of how Chesapeake authorities dealt with unwanted scoundrels.

Stede Bonnet (1688-1718)

Blackbeard’s unlikely partner in crime was a wealthy landowner, named Stede Bonnet. Nicknamed “The Gentleman Pirate,” Bonnet was born into an aristocratic British family in Barbados. Even though Bonnet had no experience in sailing, Blackbeard took him under wing, and the polar-opposites shared many a conquest along the Atlantic Coast.

The notorious William Kidd allegedly worked his way through the Chesapeake Bay, too. Originally commissioned as a British privateer, some reports suggest that he got off track and turned to piracy.

In 1700, he was arrested, shipped back to England, and sentenced to death. The rope broke during his execution, but a second attempt at hanging finished the job. For years, his body hung above the Thames River in a cage called a “gibbet,” to discourage others from choosing life as a buccaneer.

William Kidd (1645-1701)

Kidd accumulated a hefty fortune during his time on the seas, and a portion of his booty was recently discovered on Long Island. But according to legend, not all of his treasure has been found, because he buried it in various spots on the mid-Atlantic. So, the next time you anchor your boat on a remote neck of the Bay, don’t be afraid to dig in the sand and look for hidden treasure beneath your feet.

Learn More About Bay Buccaneers…

Want to read more about sea rascals who plundered the Bay? The definite resource is Pirates on the Chesapeake by Donald G. Shomette (Tidewater Publishers, ISBN: 978-0-87033-607-2). But if you’d like travel the Chesapeake waters with other buccaneers, the following tours and festivals will help you unleash your inner-swashbuckler:

- Capt. Jack’s Pirate Ship Adventures (Virginia Beach), http://virginiabeachpirateship.com, 757-305-9700

- Duckaneer Pirate Ship Tours (Ocean City, MD), http://theduckaneer.com, 410-289-3500

- Pirate Adventures on the Chesapeake (Annapolis), www.chesapeakepirates.com, 410-263-0002

- Urban Pirates (Baltimore), http://urbanpirates.com/web, 410-327-8378

- Pirate & Privateer Crews, www.noquartergiven.net/crews.htm

- Yorktown Pirate Boat Tour, www.sailyorktown.com/pirate-cruises.html, 757-639-1233

- Rock Hall Pirates & Wenches Weekend, www.rockhallpirates.com (annually in August)

- Fells Point Privateer Days, www.fellspointmainstreet.org (annually in April)